Kenya reports first local case of powerful drug-resistant bacterial gene

The implications of this finding are significant. Because the bacterium is resistant to many antibiotics, including some of the strongest available, treating infections caused by it becomes much more difficult and, in some cases, nearly impossible.

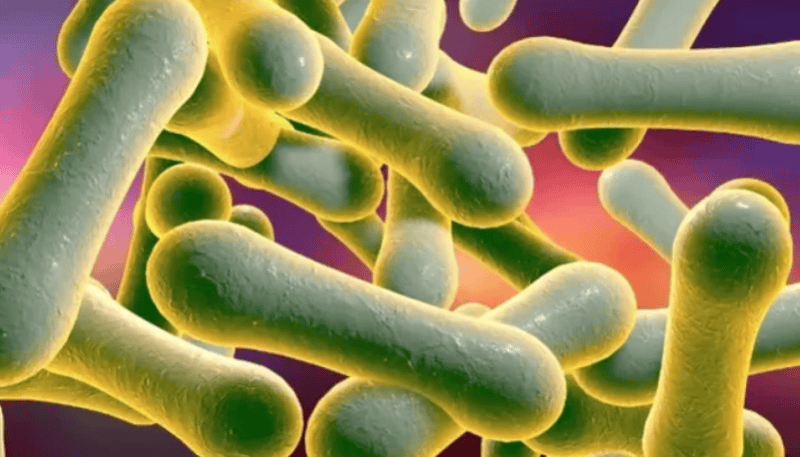

Kenyan scientists have identified a gene that can make bacteria resistant to almost all major antibiotics, representing the first time this highly concerning gene has been detected in Africa.

Experts warn that if this resistance spreads in Kenya, common infections such as urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and bloodstream infections could become very difficult to treat. While this gene has been reported in other countries, this is its first known occurrence on the African continent.

More To Read

- Ministry warns Kenyans on escalating antibiotic resistance

- DNA identifies two bacterial killers that brought down Napoleon’s army

- Your phone is covered in germs: Tech expert explains how to clean it without doing damage

- What your mouth is telling you: Saliva’s hidden clues to your health

- Why your kitchen sponge could be dirtier than your toilet seat

- Senators demand urgent Ministry of Health action on child deaths from drug-resistant infections

The study published in the Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance found a strain of Acinetobacter baumannii from a 58-year-old woman in Kenya that carried the blaNDM-6 gene. Genetic testing showed that these bacteria belonged to a rare type called ST52, which is not commonly found around the world.

The blaNDM-6 resistance gene was located on a small piece of DNA called a plasmid. The bacteria had four plasmids, and two carried antibiotic-resistance genes. The blaNDM-6 gene was part of a mobile DNA structure that can help spread resistance to other bacteria.

This discovery matters because it shows that strong antibiotic-resistance genes are now appearing locally in Africa, not just being imported from other places.

Since the gene sits on a plasmid, it can easily move to other bacteria, making them resistant too. The fact that the bacteria are resistant to many antibiotics means treatment options are very limited.

The scientists explained that the bacterium found in Kisii County carried the NDM-6 gene and was also resistant to many of the antibiotics that doctors normally use. They reported that it could not be treated with meropenem and was resistant to several other drugs, including piperacillin, ticarcillin–clavulanic acid, cefepime, ceftriaxone, and levofloxacin.

The Kenyan woman from whom the sample was taken had a pus-filled, infected ulcer on her right breast. She had already been on antibiotics for a week, including intravenous flucloxacillin, before the sample was collected.

She had not travelled outside Kenya, which means she likely picked up the resistant gene within the country. This suggests that the gene or bacteria carrying it may already be spreading quietly in Kenya.

This is the first time blaNDM-6 has been reported in Africa. Because it appeared in a rare strain, it was likely picked up locally through plasmid transfer. The finding shows that A. baumannii is becoming more drug-resistant over time. The researchers say low- and middle-income countries need better genetic monitoring to detect and control the spread of these resistance genes.

The implications of this finding are significant. Because the bacterium is resistant to many antibiotics, including some of the strongest available, treating infections caused by it becomes much more difficult and, in some cases, nearly impossible.

The fact that the blaNDM-6 gene is carried on a plasmid means it can easily spread to other bacteria, potentially creating more hard-to-treat “superbugs” in hospitals or the community.

Since the patient had not travelled outside Kenya, the gene was likely acquired locally, suggesting that this resistance may already be circulating quietly within the country.

The detection of blaNDM-6 in a rare strain also indicates that even uncommon bacterial types are now gaining powerful resistance genes, showing how quickly resistance is evolving. These findings highlight the need for stronger infection-control practices in hospitals and improved antibiotic-use policies to prevent spread.

They also show why low- and middle-income countries urgently need better genomic surveillance systems to detect new resistance genes early and stop them from becoming widespread.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a growing global problem. By 2023, about one in six bacterial infections worldwide was resistant to standard antibiotics, with resistance rising fastest in low- and middle-income regions, including Africa. Bacteria like E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae show particularly high resistance, making once-treatable infections harder to cure.

The finding is concerning and shows these bacteria are becoming more dangerous. They recommend better genetic monitoring in African countries and stronger infection-control practices in hospitals to prevent the spread of such hard-to-treat bacteria.

Bacteria carrying the blaNDM gene, which makes them resistant to strong antibiotics called carbapenems, are found in many countries around the world. They are most common in parts of Asia, especially India and China. They have also been reported in Europe, North America, the Middle East, and South America

In Kenya, AMR is already widespread. In 2019, drug-resistant infections were linked to 8,500 deaths, with 37,300 deaths associated overall. Hospital and community studies show high levels of multidrug resistance among common bacteria, indicating that AMR affects both patients and the wider population.

The rise of AMR threatens treatment effectiveness, increases healthcare costs, and makes infections harder to control. Resistant bacteria in hospitals and the community could spread widely, making routine medical care, including surgeries and childbirth, riskier. This highlights the urgent need for better infection control, antibiotic stewardship, and surveillance systems.

Top Stories Today